On Writing

Writing Serious Nonfiction Accessibly

First appeared in Women Writers, Women’s Books, February 23, 2022.

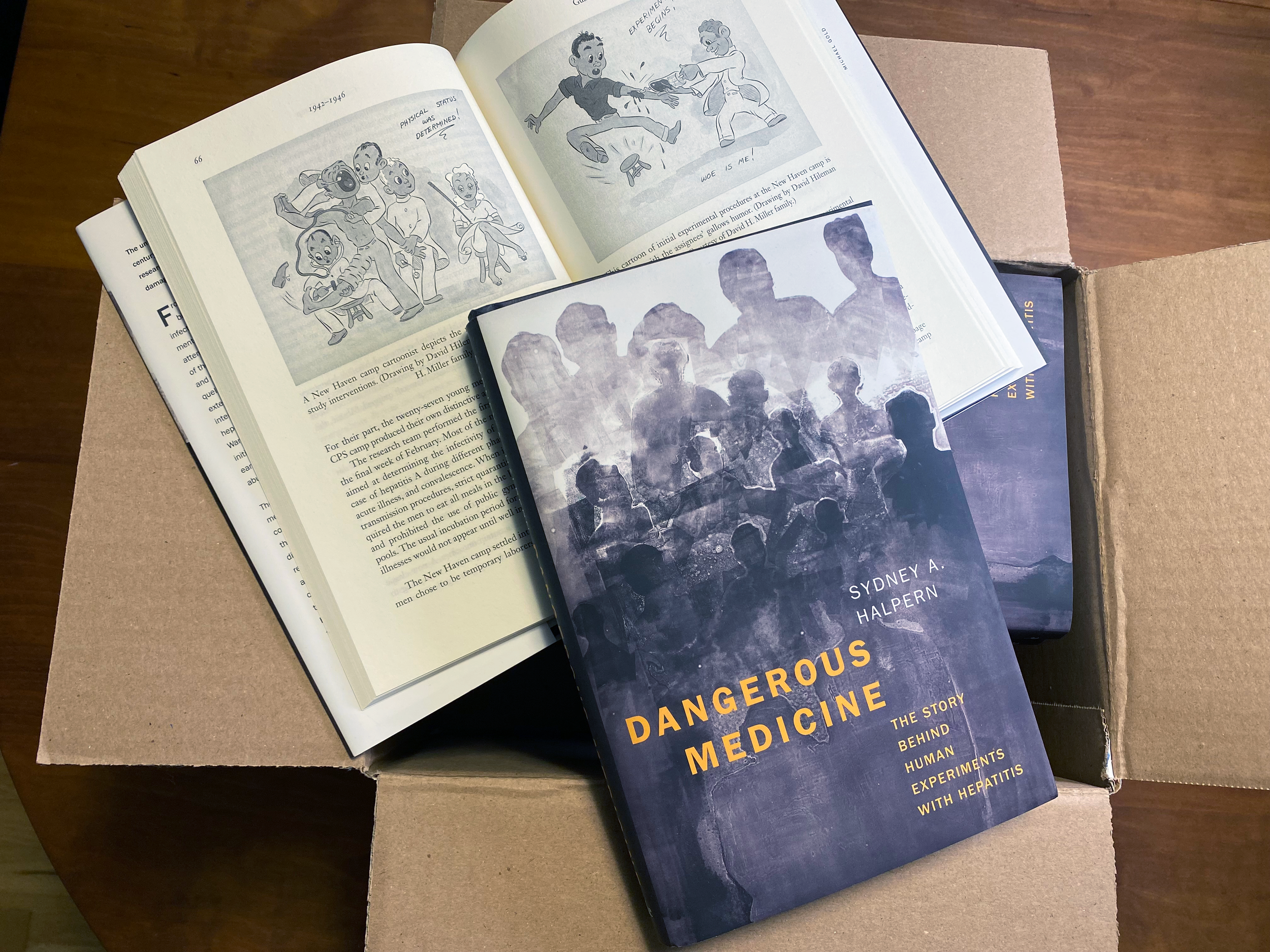

When I began working on Dangerous Medicine: The Story behind Human Experiments with Hepatitis, one of my goals was to turn thorny subject matter into a book valuable to scholars while also of interest and accessible to general readers. I was in a good position to embark on this course. I was already accustomed to crossing disciplinary boundaries: history, sociology, medical-research ethics. And as a tenured senior professor, I no longer had looming career concerns. I could write the book I wanted the way I wanted.

But producing a book effective at reaching multiple audiences—both academic and public—is no easy task. Problems arise related to the craft of writing, one’s subject matter, and the character of available sources. I talk here about some of the issues I faced and the paths I took in hopes that my experiences will be useful to other nonfiction authors.

Dangerous Medicine is about a U.S. government-sponsored research program in which researchers deliberately infected people with hepatitis. For a thirty-year span during World War II and the early Cold War, elite scientists conducted hundreds of hepatitis-infection experiments with the aims of better understanding and preventing a disease afflicting soldiers. The human subjects were all from marginalized groups: conscientious objectors to the military draft, prisoners, mental patients, and adults and children in facilities for the developmentally disabled. Some observers objected to exposing vulnerable persons to risks the studies entailed. Yet for a quarter century, scientists were successful in persuading institutional overseers and public audiences that the experiments were either in subjects’ best interests, or that participants were making voluntary sacrifices for science and country. The underlying themes here are core to both sociology and the history of medical research ethics.

But how does one convey insights from and to fields of study without the narrative getting bogged down? A good part of the answer is through writing that is clear and free of specialized jargon. It is critical to explain ideas and events in everyday language. I did a great deal of rewriting to enhance the clarity of my account and the architecture of book chapters. Meanwhile, I refrained from conventions typical in academic book writing—no heavy signposting, no headings for chapter sections, endnotes by page number and descriptive phrase without superscript numbers in the text.

Two other strategies were key in my effort to entice general readers to turn the book’s pages. I sought to make the history—its people, ideas, events, and even institutional arrangements—come alive. And I sought to tell it as a story, not as an argument.

To enliven the narrative, I included accounts of interviews with four people whose lives intersected with the research. Two were with conscientious objectors, men in their 90s, who in their early 20s served as subjects in hepatitis-infection experiments. One was with a woman who, with great reluctance many years earlier, had agreed to have her disabled daughter enroll in a hepatitis study. And one was with the daughter of a major hepatitis researcher. I reported my conversations with these individuals, their backgrounds, their views about the hepatitis experiments and the ways their perspectives represent broader themes in the book.

I also provided depictions of actors and interactions among them by drawing on a range of historical sources—archival documents, newspaper accounts, and oral histories. I describe one researcher as deeply committed to scientific medicine while adverse to conflict; another is amiable but hard driving. A young conscientious objector who emerges as a central character is sociable, garrulous, and fond of playing the cut-up. To make such attributions, it helps to have in-depth knowledge of one’s material—to own it in ways that allows confident extrapolations beyond the written record.

Another approach I pursued for animating the text was to describe locations where pivotal events took place. One of these was the National Academy of Sciences in Washington, DC. Prestigious scientists and federal medical officers met in the Academy’s Lincoln Board Room in 1942 to discuss how to end a devastating hepatitis outbreak in the military; it was there that they decided to begin human-infection experiments. I invoke the grandeur of the building’s bronze entranceway, domed hall, and stately board room as a metaphor for the social position and aspirations of America’s biomedical elite. The setting is a stark contrast to the site of the first hepatitis transmission experiment: a dismal state institution in Virginia for the developmentally disabled. The comparison underscores the vast social distance between researchers and their human subjects.

National Academy of Sciences, Lincoln Board Room. Credit: Sydney Halpern, June 2013.

I tried to give voice to the full range of actors involved in and affected by America’s hepatitis program. But some voices are missing from my story. I could find no records on the experiences of mental patients enrolled as research subjects or, except for an account from the mother I interviewed, developmentally disabled research participants. I make note in the book of this silence.

As I write this, it’s too early to tell how broad a readership Dangerous Medicine will attract. The U.S. edition of the book has been out for only three months; the British edition has just appeared. I am hopeful the book with have a wide reach and long life. In the meantime, I invite you to take a look and make your own judgment about whether my strategies for writing accessibly about serious matters have succeeded.